John Wilkes Booth‘s last stand was by no means the only infamous last stand. It got me thinking about a wide range of other events from the last couple of hundred years that might fall within the same general guidelines. Last stands happened in many places in many times. I selected a few from the multitude of instances and fixated on them.

Custer’s Last Stand, well, that would practically be synonymous with the definition of a last stand. In fact that was the first thing that popped into my mind as I expanded past Booth. Undoubtedly that notion would be the same for much of the Twelve Mile Circle audience. I couldn’t simply skip it — that would be a glaring omission — so George Armstrong Custer needed a closer examination.

Birthplace

The spot where Custer died, the place of his last stand, was considerably better known than his place of birth. I figured I’d have a difficult time finding it because I didn’t think anyone would really care except for maybe me and a handful of other people fascinated by such things. I guessed wrong. People apparently do care.

In fact I even found a Custer Memorial Association in New Rumley, Ohio, at Custer’s 1839 birthplace. They operated a small museum “open the last Sunday of each month from 1:00 to 4:00pm.” They also maintained a roadside park opened year round on the site of the original Custer homestead, of which little remained except for the foundation of the house where he was born (map).

Childhood

However Custer actually spent much of his childhood in Monroe, Michigan, with the family of his half-sister.

The people of Monroe erected a monument to Custer after his death (map). He probably got a monument everywhere he ever set foot, or so it seemed, although some hadn’t fared well. Even the citizens of Monroe, a place where he spent much of his childhood, relocated the monument a bunch of times including sticking it out in the woods where vegetation overgrew it, before moving the statue to a more prominent part of town. Officially it was known as the George Armstrong Custer Equestrian Monument, or alternately, Sighting the Enemy.

Civil War

Famously, Custer finished last in his class at the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. However it was 1861, the Civil War was just underway, and the military needed officers in a hurry so they pressed him into service anyway. He performed remarkably well once in a combat role.

“Throughout the war Custer continued to distinguishing himself as fearless, aggressive, and ostentatious. His personalized uniform style, complete with a red neckerchief could be somewhat alienating, but he was successful in gaining the respect of his men with his willingness to lead attacks from the front rather than the back.”

Custer quickly moved up the ranks, becoming brigadier general then brevet major general of the U.S. Army and finally major general of the U.S. Volunteers in quick succession. He was only 23 years old when he first became a general, the youngest in the army. Custer also served the entire length of the conflict, from Bull Run to Appomattox. At Gettysburg, he commanded the Michigan Cavalry Brigade that was instrumental in stopping a Confederate cavalry attack on the Union army’s right flank. He got a nice monument for that too. Actually, the entire Michigan Cavalry Brigade earned the monument although Custer’s image appeared in a circular bas-relief sculpture just about half way up (map).

I mentioned all of that service because people tended to overlook his distinguished career and skip right to the ending.

The Last Stand

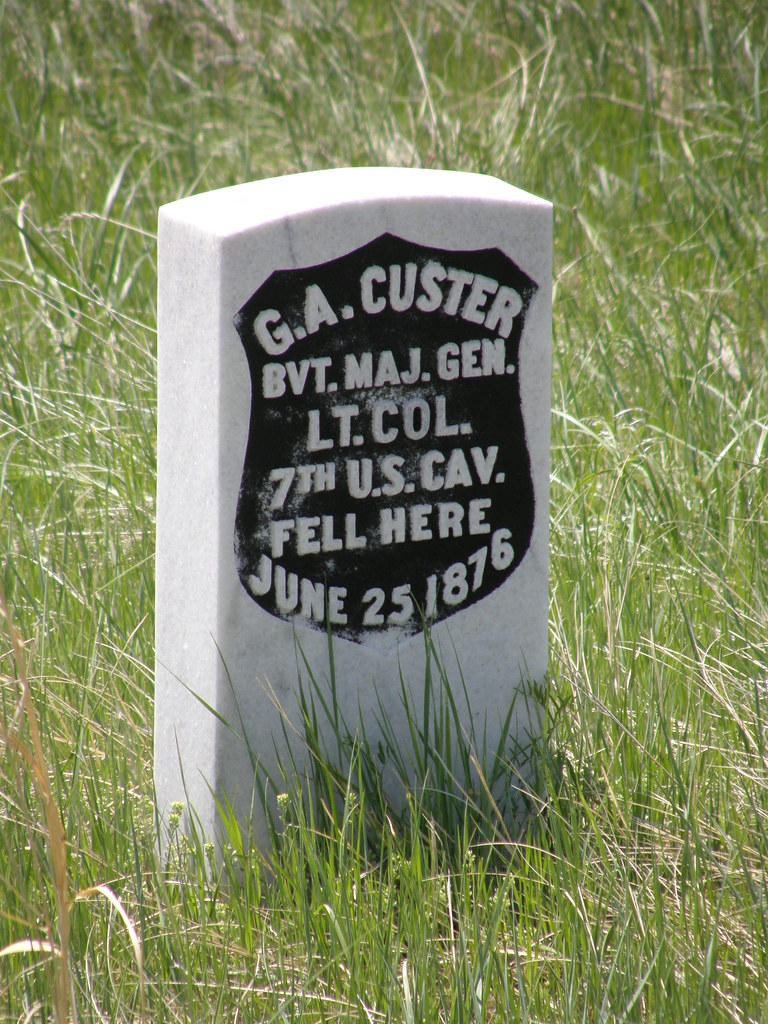

Twelve Mile Circle is not a history website so I’ll only discuss the Last Stand briefly. There were plenty of other places on the Intertubes, or even entire books, where one could get a better account. Custer died on the battlefield near Montana’s Little Bighorn River in 1876 (map). The United States Army had a rule-of-thumb, naming battles for the nearest body of water during that period (e.g., the Civil War’s Battle of Bull Run and Battle of Antietam) so the engagement came to be known as the Battle of Little Bighorn.

Heading for Disaster

The situation leading up to it brewed for a long time. The government had forced Plains Indians onto reservations for quite awhile by that point. Various elements of the Lakota and Cheyenne resisted fiercely, sparking a whole chain of events known as the Sioux Wars. The final outrage in the eyes of native inhabitants had been a sudden incursion of settlers into the Black Hills of what is now South Dakota. The Sioux considered this a sacred area promised to them in a treaty. That quickly collapsed after word leaked out about gold found in the area. Many bands, fed up with broken promises, left the reservations in an effort to fight for their ancestral lands.

The government began a protracted, coordinated campaign to crush resistance. Custer hadn’t gone out there alone, he simple commanded one force amongst several crossing the plains from late 1875 and into the first half of 1876 trying to tame the rebellion. However Custer made a huge blunder. His aggressive personality that served him well during the Civil War compelled him to rush headlong into battle without understanding the true situation at Little Bighorn.

The Endgame

He thought he was attacking a small encampment. Instead he led 700 men from the 7th Cavalry Regiment headlong into a force three times its size. Sitting Bull’s forces quickly turned the tables and utterly destroyed Custer and his men in less than an hour. Casualties also included Custer’s two brother, Thomas and Boston. Later historical accounts by members of the tribes expressed complete bewilderment that Custer would attack them when they were so strong.

George Armstrong Custer lived only 36 years.

Leave a Reply