I have a fairly neutral opinion about trains and railroads, and readers probably wouldn’t confuse me with a railfan. I never really thought about them much, honestly. Sure, I’ve taken rides on scenic railroads once or twice and related geo-oddities make it onto 12MC occasionally. However, that’s generally coincidental. I’m starting to grow more fond of them over time though. There’s plenty of weirdness on the rails.

Case in point, I talked about Bee Line railroads a few weeks ago. My interest was primarily the name; the railroad association happened to be tangential. Still, that led to an interesting comment from Dennis McClendon:

“Some 19th century railroads preferred the term “air line”… An attempt to build a Chicago-to-New York Air Line foundered on this principle. Determined to built completely straight, they spent all the construction money on an embankment traversing the first few miles of Indiana.”

Air Line?

I’d never heard of the Chicago-New York Electric Air Line Railroad before. It seemed to be a topic with a sufficient mix of geography, history and weirdness worthy of 12MC investigation. I decided to check it out.

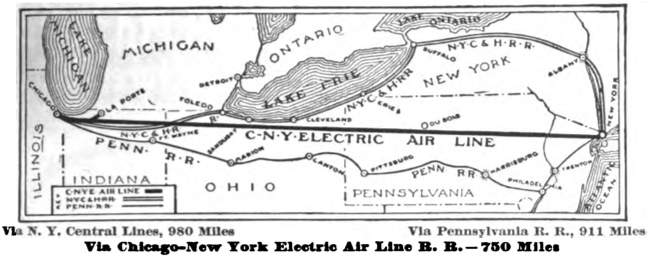

The proposed route map articulated the concept succinctly.

So the concept involved a perfectly straight line (an Air Line) from New York City to somewhere near Gary, Indiana. Then it would angle up to Chicago. It was as if someone tore a page from an atlas, pulled out a ruler, and ran a felt-tip pen directly between presumptive endpoints. The two other lines on the map showed the inefficiency of alternate routes — existing routes — and the superiority of the proposal.

Think of all the excess miles that trains could shave as long as the route tamed or ignored topography. The Air Line would feature dual tracks, eliminate grade crossings, hold track elevation changes to no more than 0.5%, and provide connections to interurban lines along the way.

An historical marker (map) outside of La Porte, Indiana commemorated this audacious plan. The marker said:

“Chicago-New York Electric Air Line Railroad. Proposed in 1905 as a 742 mile, straight-line, high speed route, without crossings; estimated ten hours travel time at a cost of ten dollars. Just under twenty miles, between La Porte and Chesterton, were constructed, 1906-1911.”

Work Began

That’s right, construction of the CNYEAL railroad actually began. It could have served as a model for high-speed rail in the United States decades before the movement rose again. The Chicago-New York Electric Air Line Railroad as proposed in 1905 envisioned an average speed of 74 miles per hour (119 kilometres/hour). By contrast, the Amtrak Acela Express came online in December 2000. It currently operates at an average speed of 84 mph (135 kph) between Washington and Boston; nearly the same result a century later.

New York to Chicago would have taken 10 hours. Today on Amtrak that same trip on the Lake Shore Limited — a route without train transfers — takes 19 hours, 5 minutes.

10th Annual Convention of the League of American Municipalities: Held at Chicago September 26, 27 and 28, 1906… (Google eBook)

Promoters gathered piles of cash through stock sales. I found this advertisement included within the material for the 10th Annual Convention of the League of American Municipalities, 1906. It promised that “capital stock of the Chicago-New York Electric Air Line Railroad is a safe and profitable investment.” However it was neither safe nor profitable. Investors lost practically everything.

Construction

So construction began with great excitement, as described in recently by the La Porte County Historical Society [link no longer works]:

“The initial stage of the proposed trans-continental electric short line took place September 1, 1906, when a special Pere Marquette of a dozen coaches from Chicago by way of New Buffalo, landed its passengers near the picnic ground on the Hall Farm in Scipio Township. President Alexander C. Miller brought with him a silver spade which was used ‘to turn the first earth in the construction of the Chicago-New York Electric Air Line Railroad’.”

A 1921 map of Scipio Township identified the location of the William A. Hall Farm adjacent to the Pere Marquette Railroad. Guess what? I found it at nearly the exact spot of the historical marker. I don’t know why the marker failed to mention that pertinent fact.

The air line only ever extended 19.6 miles “between La Porte and Goodrum, Indiana,” a fraction of the proposed 742.

Problems of Topography

Topography and mathematics killed the idea. The route needed to travel absolutely straight by definition. So builders need to conquer topographic features rather than avoid them. Design standards specified a nearly impossible one-half of one percent maximum grade. Those logical contradictions meant that any small hill, any minor creek bed would require monumental excavation, massive trestles or both.

Consider a 100 metre hill (and I think metric measurements demonstrate this better; maybe someone can double-check this): The route could climb at most one metre of elevation for every 200 metres of distance covered (rise over run) to avoid exceeding a 0.5% maximum grade. That’s 5 metres per kilometre. A 100 metre hill would require 20 kilometres of anticipation — or equivalently, a 328 foot hilltop would require 12.4 miles to build up to it. Either that or the route would require tremendous road cuts through dirt and stone.

Imagine what would have happen once they hit the mountains of Pennsylvania. My quick eyeballing of a straight line would have brought the railroad through Pennsylvania somewhere very close to a series of parallel ridges near the confluence of the Susquehanna River and its West Branch (map). These are significant barriers that would make a cut like Sideling Hill in Maryland look trivial. Then construction efforts would need to repeat this over-and-over in a lengthy procession.

The Enterprise Collapsed

Proponents and investors learned that sad fact pretty quickly once the company emptied its coffers in the first few miles. The Indiana County History Preservation Society described one of the efforts [link no longer works], at Coffee Creek near Chesterton (approx. location):

“The biggest job undertaken was the fill across Coffee [formerly spelled ‘Coffey’] Creek Bottoms, which was to extend nearly two miles. A temporary trestle here, 50 feet high at its tallest point, carried construction trains out to dump their fill. The Coffey Creek fill, while only 30 feet wide at the top, measured 180 feet in width at the bottom after the earth assumed its natural incline. A million feet of timber formed the temporary trestle, which would eventually be buried within the fill…One could stand between the rails, gaze toward the horizon and see them meet in the distance without the slightest deviation from a straight line.”

The Chicago-New York Electric Air Line failed to materialize beyond its initial twenty-mile proof of concept. A segment survived for awhile although it never amounted to anything more than a tiny part of an interurban network. Soon enough, air lines actually flying above the ground rather than hugging the rails would fill the high-speed niche between Chicago and New York.

I’ll keep Electric Air Lines in mind as people talk about the possibility of hyperloop trains. The CNYEAL could serve as a valuable object lesson.

Leave a Reply