Stockton Springs, Maine (August 2009)

It was 1759. The French and Indian War battled across North America’s eastern interior, and the British tried to protect their colonial possessions from invasion. The Governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Pownall, considered that a fort along the the western bank of the Penobscot River on Cape Jellison would be a mighty fine idea.

A permanent troop garrison at Aquahassidek (landing place) on the Cape’s Wasaumkeag Point, now called Fort Point, would prevent French access to the sea and keep them bottled up inland. It would also keep the Noridgwoak/Norridgewolks and Penobscot Indians at bay. Governor Pownall mounted an expedition leaving Boston with 400 men, intending to establishing a fort in this vast wilderness. He named the fortification after himself and it became forever known as Fort Pownall (map).

The Design

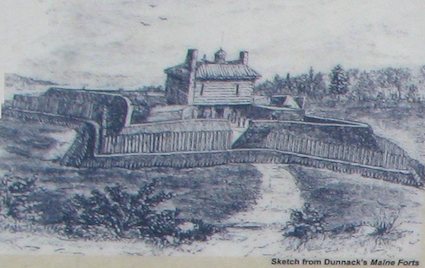

There are few primary sources that record what the fort may have looked like, but historians believe the image here (which I photographed from a sign on the site) was produced by an unknown sketcher who likely had first-hand knowledge.

A Revolutionary War veteran, Joseph P. Martin, never saw the fort but recorded an account from someone who had been there:

“It was a regular fortification, four square flankers, with a block house in the centre. It was surrounded by a ditch 15 feet wide at the top and five feet at the bottom, and probably 8 feet deep. The outer side of the ditch was 240 feet, and the brest[works] within the ditch 90 feet. A block-house was erected within the Fort 44 feet square with flankers 33 feet on the side… The block-house was of square timber, dovetailed at the corners. It was of two very high stories–the lower story used as a barraks; the upper story jutted over the lower 2-1/2 or three feet. .. In this room were 10 or 12 cannon. The roof was hipped, with a sentry box on the top. The houses of the officers were situated between the fort and the bank of the river.”

(source: Maine Department of Conservation).

History

The fort never suffered combat but it figured in several historical episodes during its brief existence. General Samuel Waldo joined Governor Pownall on that initial expedition to establish a fort. General Waldo joined a detachment using the new fort as a base to explore the surrounding countryside, and while in the field he was struck by apoplexy and died. He was buried at the fort with full military honors.

Eventually his remains were relocated, possibly to the King’s Chapel burying-ground in Boston. Today a marker rests on the approximate spot of his original grave. Waldo County, the county where the ruins of Fort Pownall are now preserved, has been named in his honor. There is also a Mount Waldo near Bucksport, its excellent granite used to construct buildings used throughout the northeastern United States, including parts of the Washington Monument, several piers supporting the Brooklyn Bridge, and the Fort Knox located in Maine.

Legacy

The mere presence of Fort Pownall had a tremendous impact on the entire Lower Penobscot watershed. People streamed into the area feeling a sense of protection and security from threats, real or imagined, from the French and the Indians. Towns sprang up all the way to Bangor and the countryside began to fill with settlers. Many of the towns in Waldo County can trace their years of incorporation to the decades immediately following the establishment of Fort Pownall.

The fort also played a bit part in the American Revolutionary War. The British Army removed its cannons in 1775. Later, the Continental Army burned it to keep the British from using it. That was pretty much the end of its usefulness.

In later times the Fort Point Lighthouse was built a few hundred yards away where it continues to stand to this day. All that remains of Fort Pownall, however, are ruins. It passed an important milestone in 2009, the 250th anniversary of its construction, an event celebrated by the nearby town of Stockton Springs.

Readers who have an interest in forts might also want to check my Forts, Fortresses and Fortifications page.

Leave a Reply