Crossing the James River near Jamestown, Virginia (October 2007)

I wanted to avoid heavy traffic on Interstate 64 during my drive to Williamsburg, Virginia, electing instead to hug the rural southern bank of the James River. It took longer and I went farther, but I wandered empty winding ribbons of rolling terrain, woodlands, plantations and fields of cotton ready to be plucked. I cut north from Route 10 through the small town of Surry, taking Route 31 towards Scotland Wharf (map). I realized I was on a great riding road when I saw touring motorcycles cruising in large clumps in both directions.

No bridge crossed the James River anywhere near this spot and it wouldn’t be feasible to consider one. An asphalt route to Williamsburg would detour another 60 miles where only a couple miles separated riverbanks. In colonial times this wouldn’t have been a problem. Rivers were highways not obstacles. Later generations relied on ferries. This continued into the present on many rural waterfronts.

Scotland Wharf

The Jamestown-Scotland Ferry doesn’t take reservations but that wasn’t a problem. I pulled onto the landing and waited in line awaiting the next boat. As I marked time I poked around Scotland Wharf, gazing across the river and watching gulls swoop and squawk along the shore.

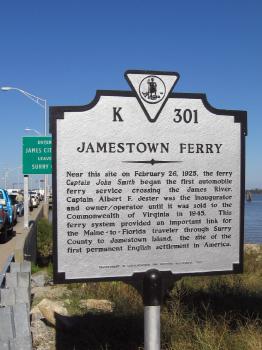

I smiled at the sign that supposedly marked the boundary between Surry County and James City County, realizing that it would have been much more memorable if they could figure out how to mark the actual border resting squarely at river center. A nearby marker gave a pocket history of how this ferry came to be:

“Jamestown Ferry. Near this site on February 26, 1925, the ferry Captain John Smith began the first automobile ferry service crossing the James River. Captain Albert F. Jester was the inaugurator and owner / operator until it was sold to the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1945. This ferry system provided an important link for the Maine – to – Florida traveler through Surry County to Jamestown Island, the site of the first permanent English settlement in America. Department of Conservation and Historic Resources, 1987.”

The Ferryboat “Virginia”

As I relaxed at Scotland Wharf still waiting for the ship, I spotted the ferryboat Virginia moored to pylons at the end of a multi-pronged dock. The Virginia got a break that afternoon. Larger boats crisscrossed the waterway, keeping up with weekend visitors heading for plantations tours and Sunday scenic drives. A ship left each riverbank twice an hour.

The ferryboat Virginia, built in 1936, held only 28 cars so it had to sit dockside awaiting slower times. That happened frequently enough. The system operated 24 hours a day, every day, including holidays. A smaller ship would suffice for the middle of the night. Larger ships would be preferable at peak times like weekday rush-hour or summer weekends.

The operation was much larger and busier than I expected, and nearly a million vehicles make the fifteen minute voyage each year. The cost for this spectacular sea passage past historic Jamestown Island? Nothing. The ferry is free. Tax dollars hard at work.

The Ferryboat “Surry”

Less than half an hour later I rolled onto the deck of the ferryboat Surry. This was a larger ship built in 1979 to transport 50 cars at once. The ship, of course, honored its namesake county on the southern shore of the James River, the place where I stood only moments earlier.

Surry County had ancient roots at least as far as North America was concerned, having split from James City County in 1652 when surrounding countryside still belonged to the Royal Colony of Virginia. Surry became the cradle of historic farms and landed gentry, of palatial rural estates with imposing names like Bacon’s Castle, Chippokes Plantation and Smith’s Fort Plantation, of great inequity between those who controlled and those who were enslaved, and of the promise of a brighter agrarian future.

A superstructure towered vertically from Surry’s otherwise low profile, her captain perched far above the navigable waters of the James. It tapered as it climbed, barely the width of a single person below, packing in as many cars as possible along the deck. A central stairwell rose up tower, leading not only to the bridge but to a sheltered passenger room behind it. This might be a cozy spot during nasty weather but hardly a necessity this day.

Leaving the Dock

I climbed the stairwell for an elevated view. I peered across the wide expanse of tidal water towards my destination at Glass House Point on the opposite bank, a low green bar on the horizon. The national flag of the United States declared its domain, raised prominently above the deck, unwavering in a refreshing sea breeze.

The ferry filled quickly with cars, trucks and motorcycles on five narrow lanes, packed bow to stern, inches to spare. Nothing separated the first cars from the river below except a retractable metal fence barely suitable for stopping people, so I hoped for small waves or at least strong brakes. That wasn’t necessary. These ships are large enough to accommodate and transport just about anything that can drive down the road including trucks up to 16 tons and tractor-trailers nearly twice as heavy.

Underway

The ship left Scotland Wharf and we found ourselves within the wide expanse of the James River. Jamestown Island drew closer into view. Here, in 1607 Captain John Smith founded the first permanent English colony in what would later become the United States, and named if for his ruling monarch, King James I.

He chose an easily defended island fortress to thwart European raiders. That became a disastrous liability for a settlement site, surviving in spite of itself on a swampy terrain of meager resources and fatal disease. Its sustainability wasn’t assured until John Rolfe cultivated a tobacco that could be exported profitably back to mother England and the colonists fanned out along the mainland.

I could begin to make out the buildings and ruins that dotted the island park, and later passed replicas of Christopher Newport’s famous ships, Susan Constant, Godspeed, and Discovery, moored dockside as tourist attractions. It amazed me that colonists crossed the wide and stormy expanse of the Atlantic Ocean voluntarily and repeatedly on those tiny boats, smaller than our ship now crossing a two-mile river.

The ferryboat fixed on an extended pier at Glass House Point, named for the nearby Jamestown Glasshouse where National Park Service interpreters blew glass in a traditional fashion, and the terminus of my journey.

Pocahontas

We passed the Pocahontas heading in the opposite direction back towards Scotland Wharf. This was the newest and largest of the ferryboats, built in 1995 to haul 70 cars across the river at a single time. It plowed through calm water, flags furled, passengers standing on the deck in the bright light of an early autumn afternoon.

As with the other ships in the fleet it carried a moniker of historical significance. The name Pocahontas is renowned worldwide in legend and literature, but the namesake Native American maiden lived just a stone’s throw from this here. Wahunsunacock, chief of the powerful Powhatan nation ruled the Tidewater region by birthright and conquest, and raised Pocahontas as a princess.

John Smith wrote that Pocahontas saved his life as he faced execution under order of the Powhatan emperor although later historians have expressed some skepticism. Pocahontas did marry John Rolfe though, and traveled to England during the final year of her life where she passed away.

Visions of plantations, tobacco, history and legend filled my head as I stood on deck, peering through four hundred years of European influence, a soft wind blowing through the air. All of this would have been lost if I’d chosen to hurl down the Interstate highway instead.

Readers who have an interest in ferries might also want to check my Ferry Index page.

Leave a Reply