Rivers can make great boundaries when they cooperate. Frequently they do not. These creatures of nature flow where they want to flow. Sometimes they erode deep furrows through solid rock, changing course only after eons pass. Other times they cross alluvial plains, shifting into multiple ephemeral streams simply awaiting the next flood. Problems will undoubtedly occur when people rely upon frequently-shifting rivers as boundaries. The shifts create winners and losers.

Two recent border situations came to my attention, handled in distinctly different ways by those involved.

The Red River

Reader Glenn seemed amused by the craziness of the border between Texas and its neighbors — Oklahoma and Arkansas — along the Red River, in an email he sent to 12MC a couple of months ago. The border rarely followed the river exactly. Actually, it reflected a version of the river that existed a long time ago. Many of the cutoffs on the “wrong” side of the river still retained names from a bygone day; Eagle Bend, Horseshoe Bend, Whitaker Bend and Hurricane Bend. Others seemed to represent the year of the flood that changed the underlying channel; such as 1908 Cutoff and Forty-One Cutoff.

Fixing the Border

Maybe I should have left it at that, a simple observation of a messed-up situation. But the decision to use the Red River as a border beginning with the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819 continues to reverberate today. This treaty between Spain and the United States addressed a host of boundary issues. A line along the Red River remained in place after Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, when Texas gained independence in 1836 and when Texas joined the United States in 1846. The river had different intentions though and meandered as it pleased.

The Red River figured prominently in a U.S. Supreme Court decision, Oklahoma v. Texas, 260 U.S. 606 (1923). The Court noted that even though the river wandered, it remained within two “cut banks” broadly defined.

“… we hold that the bank intended by the treaty provision is the water-washed and relatively permanent elevation or acclivity at the outer line of the river bed which separates the bed from the adjacent upland, whether valley or hill, and serves to confine the waters within the bed and to preserve the course of the river, and that the boundary intended is on and along the bank at the average or mean level attained by the waters in the periods when they reach and wash the bank without overflowing it.”

The Court set the boundary between Texas and Oklahoma on the south side of the Red River. Surveyors then marked and set the boundary.

The Current Dispute

Except the river kept changing while the boundary — as determined by the Court in 1923 — remained fixed. The latest dispute began within the last several years. Then it got much more complicated. While the line between Texas and Oklahoma began at the south bank, the Federal government held the portion from the middle of the river to the south bank in public trust for Native Americans. This formed a narrow strip, a 116 mile (190 kilometre) ribbon. Much of that strip is now on dry land. The U.S. Bureau of Land Management estimated that 90,000 acres actually belong in the public domain, and not to the people living there who farmed or grazed their cattle there for the last century. Lawsuits continue to rage.

The River Meuse

Reader Jasper sent me a heads up that Belgium shrank and the Netherlands grew on November 28, 2016. The two sides came to an amicable agreement and adjusted their common border.

Didier Reynders of Belgium and Bert Koenders of the Netherlands signed a treaty in Amsterdam, in the presence of their respective monarchs, King Philippe and Queen Mathilde, and King Willem-Alexander and Queen Máxima. The announcement came in a Press Release with coverage in local media (Google Translation of an article in Flemish).

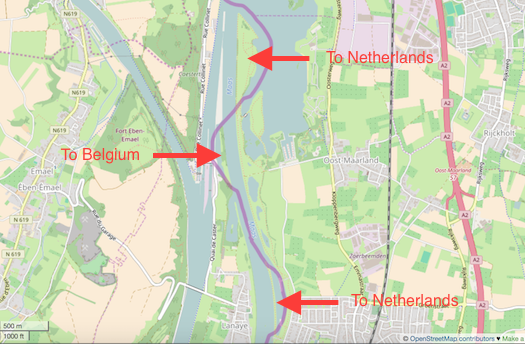

The areas in question fell along the banks of the River Meuse, forming a portion of the boundary between the two nations. They established their original border there in 1843. However, these neighbors decided to straighten their common river to improve navigation in stages between 1962 and 1980.

This left a piece of the Netherlands and two pieces of Belgium on the “wrong” side of the river between Visé and Eijsden. Police could not access these spots easily and they became havens for illegal activities. This included a situation where a headless body washed ashore on one of the exclaves. Territorial complexities hampered the investigation.

In an unusual twist and in a supreme act of neighborly cooperation, the two nations simply agreed to swap their stranded parcels. It seemed the most logical option, and yet, it remains exceedingly rare in other border situations worldwide. Nobody wants to be the loser. Belgium simply gave up 14 hectares (35 acres) in the deal and called it good.

Leave a Reply