Every once in awhile I receive a tip where I need to drop everything so I can search for an explanation. Frequent reader “Aaron” discovered an exclave that I’d never seen before. Shockingly, it appeared in my own home state of Virginia and I’d actually driven through the exclave during my county counting adventures. How did I not notice it?

That’s all it took to suck me down into a rabbit hole for most of a Saturday afternoon.

The Exclave

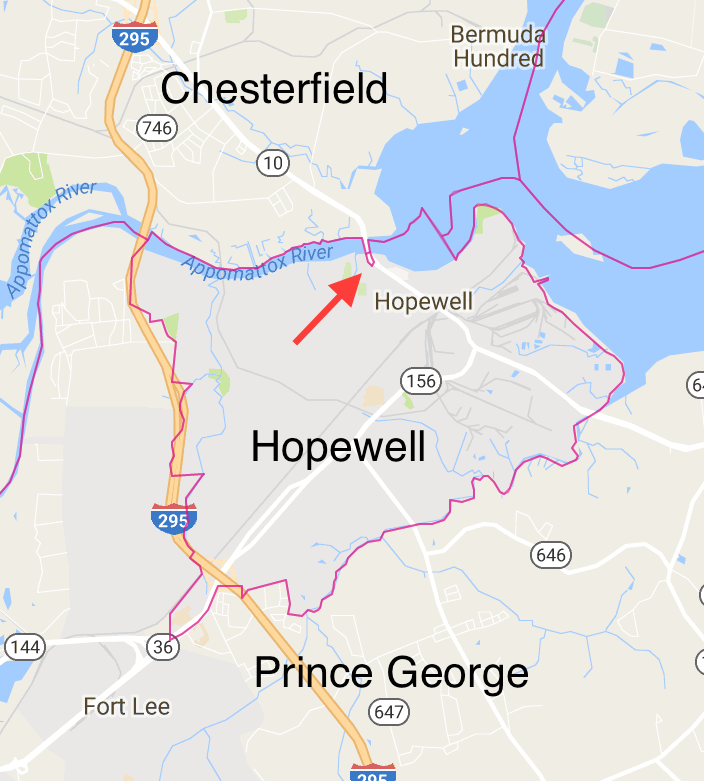

The exclave definitely existed. I examined several sources and found it each time. Check it out:

Virginia’s independent city of Hopewell carved its territory from the northwestern corner of Prince George County, at the confluence of the Appomattox and James Rivers. Prince George surrounded Hopewell on three sides — east, west and south — while Chesterfield County hugged its northern shore across the Appomattox.

However, a tiny dot of Prince George stood alone, stranded from the rest of the county. This overlapped a segment of Virginia State Route 10, Randolph Road. Someone driving south from Chesterfield along the road would first hit Prince George (sign) and then enter Hopewell (sign) only 0.32 miles (0.5 km) later. This wasn’t an inconsequential road either. It supported an Annual Average Daily Traffic Volume of 19,000 vehicles.

This brief slice of Prince George coincided with a bridge across the Appomattox, from the river midpoint to where the bridge returned to dry land. The exclave formed a rectangle no wider than the bridge itself. I will visit it someday. Fortunately there appeared to be a safe point to explore it, on Riverside Avenue directly below the bridge. That, of course, fell within the exclave too.

Annexation by Independent Cities

The Commonwealth of Virginia maintained an odd assortment of independent cities, a highly rare arrangement within the United States. Of the 41 independent cities found in the U.S., 38 of them fell within Virginia (only the cities of Baltimore, St. Louis and Carson City did not). I’ve mentioned this anomaly several times in 12MC over the years, usually in reference to my county counting pursuits. Those independent cities were not subservient to their surrounding counties and thus they “counted” as county equivalents.

I hadn’t looked much at the mechanics of it until now. Fortunately I found a publication from the University of Virginia’s Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service. The arrangement extended all the way back to Virginia’s colonial era, an artifact carried over to modern times. Cities could annex land from adjacent counties as needed. However, counties generally did not like to cede their territory.

This situation begged for an equitable process so the General Assembly adopted revised procedures in 1904. It required a proposed annexation to go to a special court composed of three judges who would listen to both sides before making a decision. The court approved about 80% of annexations over the years according to this publication. Virginia recognized 128 of 160 proposed city-county annexations until it implemented a moratorium in 1987. Annexations caused too much animosity between cities and counties to continue.

Hopewell incorporated as an Independent City in 1914. Thus, it followed the 1904 procedures. The 3-judge panel would have adjudicated Hopewell’s formation and any expansions. The resulting exclave must have been an explicit and intentional act on Hopewell’s part. So there must have been a specific reason for Hopewell to exclude that tiny sliver of Prince George. It was not an accident.

Byrd Road Act

Then what might have been the reason? I found a likely candidate in some Depression-era legislation, Chapter 415 of the 1932 Acts of the General Assembly. This was more commonly called the Byrd Road Act. Harry Flood Byrd controlled Virginia politics for a half century through his Byrd Organization, a powerful political machine. He served as governor from 1926-1930, then as a U.S. Senator from 1933-1965. The legislation in question focused on secondary roads, enacting Byrd’s vision even though he no longer served as governor.

The Depression hit Virginia’s rural counties particularly hard. They didn’t have enough money to pave most of their roads, much less maintain them. They Act offered a novel solution. Control of secondary roads reverted to the state at the discretion of each county. State tax receipts would then fund construction and maintenance. An estimate at the time predicted that the Act “would reduce rural taxes by $2,895,102 annually.” This seemed like an excellent trade-off and nearly every county accepted the offer (and today only Henrico and Arlington Counties control their own secondary roads as a result).

However, money had to come from somewhere. The Act excluded independent cities which still had to maintain their own secondary roads. Additionally, more people and more wealth concentrated in cities. Therefore state taxes paid by city residents subsidize road construction and maintenance in counties.

Cities got hit twice, once for their own roads and again to support rural roads throughout the state. That was just fine by the Byrd Organization which found its base of power in rural counties. Even today people marvel at the wonderful, beautiful roads in the middle of nowhere throughout Virginia. Thank the Byrd Road Act.

Conclusion

Now, back to that bridge carrying drivers on Route 10 across the Appomattox River. If Hopewell annexed the land and water beneath the bridge then Hopewell’s taxes would have to maintain the bridge. If Hopewell declined to annex the bridge — leaving behind a tiny pocket of Prince George County — the state of Virginia would have to maintain it. That created a powerful financial incentive for Hopewell to exclude the bridge from its annexation proposal. Prince George County wouldn’t care. It wouldn’t have to pay for maintenance regardless.

I never found an official government document that said explicitly that this was the reason. However, I believed a preponderance of the evidence pointed clearly towards that direction. It made perfect sense and no other reason seemed plausible.

Ironic Addendum

Virginia’s counties got a great bargain in 1932. However, the system began to fray over the decades especially for rapidly urbanizing counties. A report published by George Mason University in 2011 concluded,

“Almost one-third of Virginia’s secondary road system is currently deficient, and programs designed to attract county participation in construction and maintenance are not working… the Virginia Department of Transportation’s (VDOT) secondary construction program has provided minimal funding support for constructing new secondary roads in recent years…”

Some localities, like Fairfax County with over a million residents, began to chafe under a system where the state controlled its secondary roads. Insufficient, traffic-clogged roads threatened to strangle the county with gridlock. Fairfax even began to explore conversion to independent city status in order to regain that control.

One Final Note

A special thank you to Aaron. This page now serves as the definitive source of information for the maybe ten people on the entire planet who want to know about this exclave. I can’t believe I spent nearly 1,200 words talking about a plot of land only a third of a mile long by a hundred feet wide. That’s why you read Twelve Mile Circle. Right?

Leave a Reply