I’ve slowly been overhauling the non-12MC part of my website to upgrade to Google Maps API v3. That’s the portion for which I obtained the howderfamily.com domain long before Twelve Mile Circle became the tail wagging the dog. As part of that I revisited a genealogy page I wrote about ten years ago. It looked like it could use a map so I made one.

It reminded me that I’ve had it pretty easy when we visit the in-laws in Wisconsin. The flight takes an elapsed airtime of about an hour between airports, so no big deal. My ancestors undertook a journey of similar distance when they moved from Maine to Wisconsin in 1844. And they seemed pretty satisfied that it took “just one month.”

The family patriarch described the entire journey in a letter that he sent to his brother back in Maine. I received a copy of the letter in 2002 and wrote about it in a genealogical society journal. The resulting article is reproduced elsewhere on my site if you’re interested. It includes a lot of family history content so feel free to skip it. Instead I’ll focus on what will more likely interest the 12MC audience, the geography and logistics of a North American journey in the 1840’s.

I took a much closer look at the letter this time around so I could design a reasonable replica of the route. The letter contained several place names, a few actual dates, and a verifiable historic event. All of these allowed me to reconstruct a full sequence of steps including even the days of the week. I could determine with near certainty that the journey began on Saturday, October 5, 1844 in Phillips, Maine and concluded a month later on Tuesday, November 5 in Jamestown, Wisconsin.

Markers on the map include supporting text from the letter. Colored lines represent changes in transportation modes.

Phase I – Cart and Foot: October 5-7

The journey began by hauling the family and its freight down to a port. The group then stopped to visit with some relatives along the way. Thus it took three days to get to the nearest river town with ocean access. The port was just outside of Augusta, the capital city of Maine on the Kennebec River.

Phase II – Ship: October 7-8

They sailed down the Kennebec River into the Gulf of Maine, hugged the coastline and entered Massachusetts Bay. Then they disembarked at Boston, Massachusetts.

Phase III – Railroad: October 8-10

The Boston and Albany Railroad received its charter in 1831 and laid its track westward in phases. One could travel the entire route between the two cities by rail beginning in 1841. The family took early advantage of this transportation innovation to hasten its movement across Massachusetts.

The letter never mentioned a railroad explicitly. However, no other transportation method could have covered the same distance in a similar amount of time. It referenced a three hour segment between Boston and Worcester for example, a distance of 46 miles. A stagecoach would have averaged 5 miles per hour. A typical speed for a train in the early 1840’s would have been about 10 to 20 miles per hour.

A rail line existed, the speed of motion matched historical averages for trains of that period, and towns mentioned in the letter (where the family stopped) mirrored the Boston and Albany Railroad route. The facts seem to fit.

Phase IV – Canal Boat: October 11-18

Nothing moved faster overland than a railroad but routes were still a novelty in the early 1840’s. Rail hadn’t become a ubiquitous form of transportation like it would a couple of decades later. Thus the family had to find another option to move forward. Waterways were still the superhighways of the era, and New York had a great one. The 363 mile (584 km) Erie Canal opened in 1825.

It took the group a full week to cross New York. That duration was consistent with Erie Canal averages. Boats traveled at about 4 miles per hour (6.5 kph), with rest stops and additional time to traverse dozens of locks that often became choke points.

In one of life’s odd coincidences, my mother’s side of the family (in a canal boat) and my father’s side of the family (farmers living near Lockport) came within amazingly close proximity of each other. This happened on or around the evening of Thursday, October 17, 1844 — literally a “ship that passed in the night”. The families wouldn’t get another chance for more than a hundred years and in a completely different location.

The canal boat docked in Buffalo, New York on the shores of Lake Erie.

Phase V – Great Lakes Steamship: October 21-26

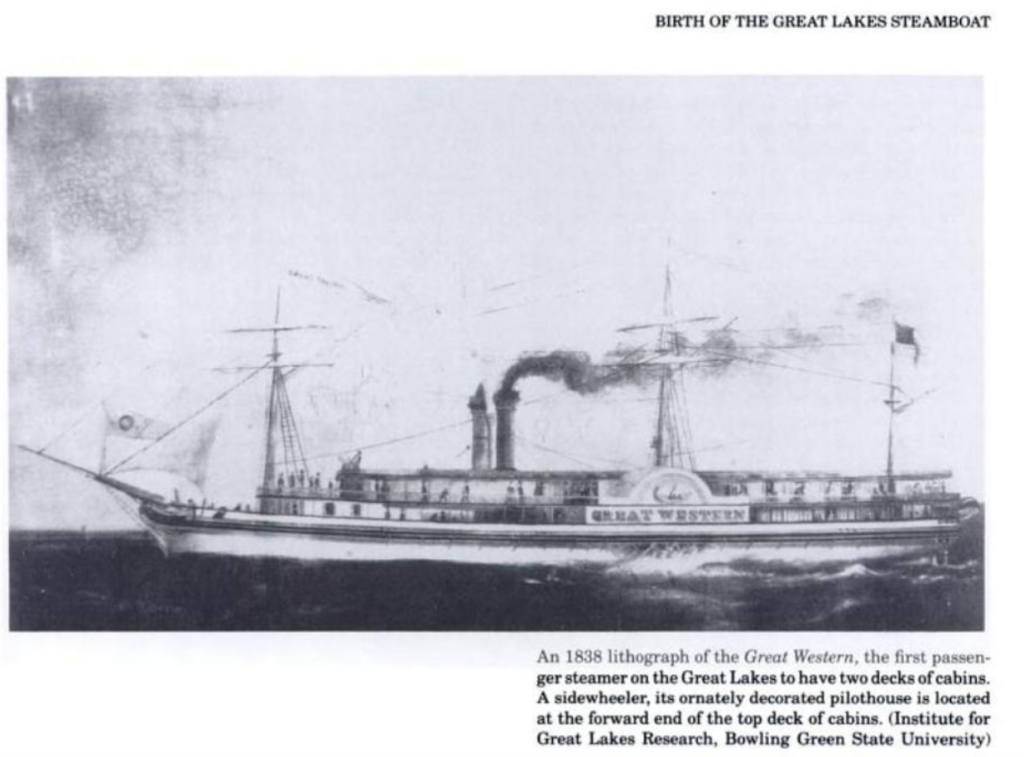

Once again it was logical that the family would take advantage of a waterway. The first commercial steamboat services began in the first decades of the 19th Century. Therefore they were quite common by the 1840’s. The Great Lakes were filled with them.

Here the family narrowly averted a calamity. They had the misfortune of arriving in Buffalo on the afternoon of Friday, October 18. Four steamships were ready to set sail that evening but they were already crowded with passengers. The family wasn’t in a hurry so they decided to wait until the next morning. A huge storm with hurricane-force winds hit that night and it lasted into the following day. It was so severe that it is still remembered historically as the “Lower Great Lakes Storm of 1844”.

As described in the History of the Great Lakes, Chapter 36:

“For several days before the occurrence of the flood a strong north-east wind had been driving the water up the lake, but on the evening of the 18th a sudden shift of the wind took place, and it blew from the opposite direction with a tremendous force, never before or since known to the inhabitants of Buffalo. It brought with it immense volumes of water, which overflowed the lower districts of the city and vicinity, demolishing scores of buildings, and spreading ruin along the harbor front, playing havoc with shipping, and causing an awful destruction of human life.”

The family escaped unscathed and was able to resume its journey the following Monday on the steamship Great Western. It took less than a week to arrive in Chicago.

Phase VI – Cart and Foot: October 30-November 5

The family decided to rent a hotel room and rest in Chicago for four days. Then they purchased “a wagon and a span of horses” and continued onward for the final leg of the journey. It took 6 days to cover approximately 180 miles (290 km) to their new home. So they traveled about 30 miles (48 km) per day during this period. They described it as “the most fatiguing and expensive of our journey.”

The family arrived in Jamestown, Wisconsin, their final destination, pretty much exactly a month after they left Phillips, Maine.

I’ll keep that in mind the next time I fly up to Wisconsin and complain about an airport weather delay.

Leave a Reply