I mentioned Brian Brown’s wonderful Vanishing South Georgia website previously as I explored leaf-vein patterns left behind by swamp drainage. Brian uses an interesting minimalist approach. It allows imagery to portray a wistful almost melancholy longing for a heritage slowly slipping away. He’s attempting to preserve it all visually before it decomposes back into the soil. I visit the site frequently and let each new crop of images stir my imagination as I click through his prolific updates.

I stumbled across an oddity there a few weeks ago, the tombstones of William Simons and George Sherman. They were two Civil War veterans from the Union cavalry now resting for eternity in a rural south Georgia cemetery. I remarked at the time that they must have met with a tragic and unfortunate demise; having found themselves interred half a continent away from their northern homelands.

Generally that would have been a safe bet. Hundreds of thousands of men died of wounds or disease over this horrific four-year conflict, but that’s not what happened to these two men. This tale takes a stranger twist. It turns a stereotype on its head. It challenges our assumptions of what we thought we knew about the Reconstruction south.

Street Names

This is Fitzgerald, Georgia, the seat of Ben Hill County. The two veterans rest in the Union section of Evergreen Cemetery on the southeast side of town.

Drill down into the map. Did you notice anything peculiar about the street names? Start with the the north-south route through town at the middle of the map, Main Street. Read the vertical street names towards the west: Lee; Johnston; Jackson; Longstreet; Gordon; Bragg; Hill; and Merrimack. Everything looks fine here. It’s a nice list of Confederate generals plus the southern contribution to the famous duel between ironclad vessels. There are no surprises here. This is the Deep South.

Now go back to Main Street and read towards the east: Grant; Sherman; Sheridan; Thomas; Logan; Meade; Hooker; and Monitor. These are all Union generals and a Union ship. Those names still trigger feelings of resentment and even anger within certain communities across the South. However, in Fitzgerald, Georgia they’ve named streets after them!

Sherman Street? You know, March to the Sea? Aren’t those fightin’ words?

The Explanation

As Brian explained to me, Fitzgerald was founded in 1896 by a newspaper man from Indiana. He intended it as a refuge for Union veterans so they could live out their lives tranquilly, away from harsh northern winters. An exodus of several thousand men and their families from all over the Midwest heeded the call.

They relocated to an underdeveloped corner of Georgia with the blessing of the Governor. The state saw it as a means to attract a group of industrious people and perhaps help heal the wounds of a divided nation. So the Yankee settlement formed and became known colloquially as Colony City. Naturally people expected the worst from such an odd mix of intractable foes. However the Yankees and Rebels, once bitter enemies, found a way to live peaceably, side-by-side.

Confederates in the Attic

Brian also recommended a book by Tony Horwitz, “Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War” specifically for its description of Fitzgerald, Georgia on pages 331-335. It provided a brief summary of life in Fizgerald from its founding days through the present. It also described the initial gathering of old Union and Confederate veterans to commemorate the war. That single event set a tone for the remainder of the town’s history:

“…so they planned two parades, one for Union veterans, the other for Confederates. But when the band began playing, veterans of the two armies spontaneously joined and marched through the town together. Thereafter, they merged to form Battalion One of the Blue and Gray and celebrated their reconciliation annually.”

I have a permanent collection of half-read books scattered throughout my home. My intentions are always noble but I’m easily distracted. I surprised myself by reading not only the five Fitzgerald pages but the rest of the book as well. That’s why it has taken me awhile to write this post. I’ve never had to do a “book report” to prepare myself for an article on this blog before. But it was an enjoyable diversion and a solid recommendation from Brian.

Insights

A decade may have passed since its publication but its themes still resonate. The book explored the continuing ties between the long-concluded Civil War and modern Southern culture from several different perspectives and viewpoints. I identified with many of his observations.

I grew up in the South (rural Virginia in my case) during a certain time and place. Until I read the book I was unaware of how often the Civil War crept into my own thoughts, consciously or otherwise. Then I was a bit surprised to see how often I’ve mentioned the war on my website even though it took place nearly a century and a half ago.

I had been to nearly every location Mr. Horwitz described in his book except for a few of the small towns. I knew enough of the landscape to recognize the exact, precise geographical placement of his rural hamlet in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains where he lived as he wrote. Well, it was actually the Catoctins, but lets not get too technical. Then I realized that the bullet-ridden church that he described near his home was the same one where I helped out with vacation bible school during quiet high school summers.

Other times I felt a sense of disappointment. I recognized that Mr. Horwitz sometimes needed to highlight extremes in personal behavior bordering on stereotypes to prove his point. The world of redneck biker gangs, devout attachment to the Confederate flag, and a sense of a long-gone past as being preferable to the future did not play familiar roles in my upbringing.

Sure I saw my share of stars-and-bars flapping in the breeze, confederate monuments in front of the county court house, characterizations of the War of Northern Aggression and talk of “the South rising again,” but that didn’t define who I or the people around me became. That aside, I agreed with his central premise. I read the entire narrative and that’s a pretty big endorsement coming from me, the infamous Mr. Short Attention Span.

Genealogy

I have another fascination in addition to my interest in strange geography. So I put those skills to use to provide some more details around the names on those two tombstones. If ever one doubted that massive paper trails follow us around for our entire lives and beyond, realize that it took me only a few minutes to consult just a few resources for people who passed away nearly a century ago. Imagine how much information you are leaving in your wake in this digital age.

Facts come from Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System, the 1890 Special Schedule of Surviving Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, and Widows, and the 1900 Decennial Census. This only scratches the surface of what is probably available.

William A. Simons

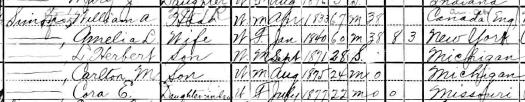

William Simons was born in April 1833 so he wasn’t a youngster when hostilities commenced. Originally he came from English Canada. However his father was born in New York, and the family moved back to the United States when he was six. William lived in Michigan at the start of the war. Then he married his wife Amelia, his life-long spouse, about the same time he enlisted in the army. They remained apart for three years as William fought across the Deep South.

William served as a Private in Company E., 4th Michigan Cavalry, from August 9, 1862 through June 30, 1865; wall-to-wall through the entire regimental history of his unit. He mustered in at Detroit and maneuvered constantly through the Southern campaigns. So he participated in conflicts at Chickamauga, Kenesaw, the Siege of Atlanta, and the capture of Jefferson Davis, plus minor conflicts too numerous to mention. He escaped wartime wounds but contracted a debilitating stomach inflammation that plagued him for the remainder of his life. Then he returned Michigan after the war. One home, he raised a family with Amelia, living in Bay City for at least part of the period

William had already lived a long, full life by the time he brought his wife and two of his adult sons to Georgia. They settled down, tilled the land and assimilated. At least one of the sons got married in Georgia and continued to reside there. William passed away sometime before 1910, which we can surmise because his wife was listed as a widow at that time.

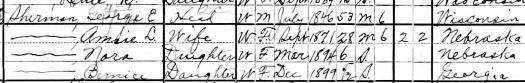

George E. Sherman

George Sherman was born in Wisconsin in July 1846 and he signed up for the war just about as soon as he was eligible. He served as a Private in Company H., 1st Wisconsin Cavalry, from February 17, 1864 through July 17, 1865. As a member of that unit, he witnessed constant action across Georgia, Kentucky and Tennessee. He also participated in conflicts at Kenesaw Mountain, the Siege of Atlanta and the capture of Jefferson Davis. After the war he located in Nebraska, got married and had a daughter. The family later moved to Fitzgerald and had another daughter. The assimilation process began in the first generation for the Sherman family.

Of note, and as mentioned, both men participated in the capture of Jefferson Davis. At the time the renowned President of the Confederacy was attempting to flee westward to rally Confederate troops stationed in the Western Theater to continue the rebellion. This took place outside of Irwinville, Georgia, barely ten miles away from where Colony City arose thirty years later. Whether by design or by coincidence, wartime service and reconstruction came full circle geographically for these men during their lifetimes.

Wild Chickens

If you’re sill reading, I have to mention one more thing about Fitzgerald, Georgia. This has nothing to do with its unique Civil War heritage. It’s the home of the Wild Chicken Festival which was held this weekend! What is the Wild Chicken Festival, you ask? I’ll let the festival organizers tell the tale:

“Back in the 1960’s, the Georgia Department of Natural Resources stocked Burmese chickens all over the state as an additional game bird to be hunted like pheasant or quail. These tiny, colorful birds resemble fighting game chickens, sporting brilliant orange and yellow ruffs and gleaming black tail feathers. Flocks of chicks were released several miles from Fitzgerald at the Ocmulgee River. Populations of the bird never took hold in other areas of the state, but for some reason, they left the river site and made their way to downtown Fitzgerald, where they have propagated and prospered ever since!”

I’d love a comment on this post if anyone happened to attend the festival. Anyone who has read Twelve Mile Circle for even a little while knows that I am not being sarcastic when I say that I wish I could have been there. I love wild chickens!

Leave a Reply