Immigration and the fingerprints it leaves behind sometimes finds its way to Twelve Mile Circle as a topic of conversation. The legacy remains even after a successful assimilation and disbursement of the original population. I’m curious particularly about the smallest populations of settlers in new lands — and it might be difficult to get more obscure than Icelandic Mormons that I discussed previously — although I continue to remain fascinated by the topic. It seemed challenging to find a population small enough to be obscure while large enough to leave behind a measurable legacy.

Suitability

Belgians in the United States. That seemed promising. A small nation of about ten million citizens would certainly limit the pool. It didn’t have a noted tradition of sending huge percentages of its population oversees à la Ireland. Additionally, it didn’t have an enormous geographic footprint like the Germanic-speaking areas to its east. The ethnic division between French (Walloon) and Dutch (Flemish) also presented interesting possibilities. Belgium became a good bet; small enough yet large enough.

Recognize that Belgium also didn’t exist as a nation until 1830. Prior to that, immigrants and settlers from this part of the world would have been from Southern Netherlands or some other geographic entity. That offered an interesting tangent. However, I don’t believe it makes much of a difference for my purposes. Place names that settlers brought with them and then transplanted upon the American landscape tied back to towns and cities that already existed by 1830.

Some 345,379 people in the United States identified Belgian ancestry in the 2010 Census. Unfortunately I could not find a way to break them down by state, although breakdowns could be derived from the earlier 2000 Census. It placed the highest concentrations of Belgian-Americans in Wisconsin, Michigan and Illinois. Additionally, Wikipedia included a page devoted to Belgian-Americans, confirming for the umpteenth time that truly every topic exists on the Intertubes. It tracked closely closely with the Census results and noted population concentrations in several additional states.

Settlement

One begins to notice patterns by cross-referencing these data with the U.S. Geological Survey’s Geographic Names Information System. I started with a very simple and obvious query to check for populated places actually named “Belgium.” It returned locations in Illinois, West Virginia and New York. Illinois shouldn’t be a surprise based upon Census reporting.

West Virginia

Also, West Virginia received a tantalizing mention in Wikipedia although it didn’t provide further detail. For that, I turned to the West Virginia Encyclopedia:

“During the first decade of the 20th century, French was frequently spoken on the West Virginia streets of such communities as South Charleston, the North View section of Clarksburg, and the small town of Salem. These neighborhoods shared a connection to the window-glass industry, and the people speaking French often were Walloons, or French-speaking Belgians. About 1900, changes in window-glass manufacture brought thousands of immigrants from the Charleroi area of Belgium just when the industry was expanding into West Virginia to take advantage of cheap natural gas and large deposits of silica sand. For a generation, window-glass factories, many of which were worker-owned cooperatives, relied heavily on these Belgian immigrants to provide the skills necessary to make West Virginia a national center of production.”

The town of Belgium, West Virginia falls right in that same general area as Clarksburg and Salem. I’d consider that indicative of fingerprints left behind by an immigrant community.

New Netherlands Colony

I couldn’t find anything about Belgium, New York other than its location. That one remains a mystery. However I discovered several other Belgian place names a bit further north in Jefferson County including Antwerp and Rosiere. It seemed to imply a settlement pattern. People from areas of the Low Countries now associated with modern Belgium became some of the earliest Dutch-era colonial settlers of New York. A larger colonial association with the Netherlands seemed to mask some of their impact. It all appeared a bit murky because a lot happened in the Seventeenth Century so I can only speculate. More research may answer this.

Upper Midwest

Then I examined a later cluster. A great period of immigration into the United States began in the Nineteenth Century. At that time the focus shifted to those states flagged by the Census, principally Wisconsin, Michigan and Illinois. Wisconsin truly became the epicenter. In fact, it concentrated within one tiny corner of Wisconsin along the Green Bay side of the Door Peninsula.

Here, one can drive from Brussels to Namur to Rosière in twenty minutes. Belgium might be a small country, but even there that same feat requires closer to an hour and a half. French-speaking Wallonian immigrant farmers transplanted the geography of their homeland. Then they squeezed it down to fit within the comforting confines of their new community. Another community clustered just down the road in Ozaukee County. This one included former residents of the french-speaking Belgian province of Luxembourg (not to be confused with the Grand Duchy of the same name).

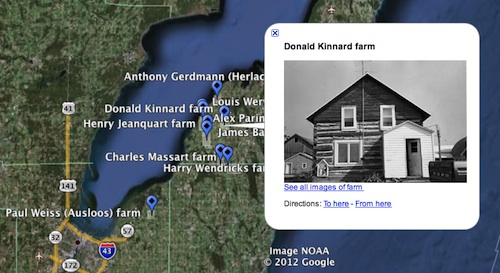

Wisconsin’s concentration of Belgian immigrants became significant within the state. It even warrant a separate Belgian-American Research Collection within the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections. This included a Keyhold Markup Language (kmz) file suitable for Google Earth. I took a screen print:

Another well-organized community existed in Michigan. I didn’t find quite as much information on that one. However, it still maintains a Belgian-American Association near Detroit as it has since 1927.

Most of the Belgian immigrant impact upon U.S. place names appears to be associated with French-speaking Walloons. I’m not sure I can claim that definitively, however circumstantial evidence seemed to point in that direction.

Leave a Reply