Don’t worry, this will be the final installment of the Ireland odyssey. I appreciated everyone wading through my personal indulgences so I saved the best for last, the Irish adventures that came closest to standard 12MC content. A couple of them are genuine geo-oddities.

Inch Beach

I mentioned Inch Beach (map) a few weeks ago in an article about sand spits, and I even threatened to visit the strand for a photo. So that’s exactly how it unfolded as I drove onto the Dingle Peninsula, and then towards the famous Inch Beach, the Dangle of Dingle.

Longtime reader “wangi” commented on that earlier article, noting “One of the Scots Gaelic terms for an island, innis, is frequently Anglicised as inch in Scottish place-names. I imagine same is true in Ireland.” I developed an alternate theory during my personal visit. Inch Beach was literally an inch wide. I captured photographic evidence.

Well, maybe it’s an inch and a half.

Tripoint

Tripointing didn’t seem to be much of a “thing” in Ireland. I could be wrong although I failed to find any Internet interest in places where three Irish counties joined together at a common point. I did notice, however, that my great-grandfather’s boyhood home in Mountcollins fell remarkably close to the Cork, Kerry, Limerick tripoint, which I dubbed COKELI in the normal naming convention. Paradoxically, this appeared to be the first time COKELI had ever been used in that context at least according to Google. I did learn that Cokeli was a mans’ name, a variant of Coakley, meaning “from the charcoal meadow.” That was an interesting etymology although it had nothing to do with tripointing, of course.

Yes, after spending a long day touring family history sites with distant relatives, I diverted my wife, kids and father slightly out of our way to find the COKELI tripoint (map). Not only did local jurisdictions mark the point, they’d reserved a small adjoining greenspace with a picnic table and a thatched-roof shelter dubbed Three Counties Park. Just don’t mess with the thatch. They don’t like that.

The marker on an old piling also implied that there was once a bridge that crossed directly over the tripoint on the River Feale (the current bridge crossed only between Counties Cork and Kerry a few metres farther south). I was surprised. Maybe Ireland contained more tripoint treasures? It also dawned on me that maybe my geo-oddity fascination might have been ancestral. Perhaps some ancient family legend or memory of this spot somehow sparked my appreciation of geographic anomalies.

County Counting

I didn’t find any Irish county counting sites, either. Maybe that’s because it wouldn’t be much of a challenge. Notice my personal county counting map of Ireland after two weeks. And I wasn’t even trying, really. A more conscientious effort certainly would have eliminated the Cork City and Co. Offaly doughnuts.

My tally: Clare; Cork; Dublin; Fingal; Galway; Galway City; Kerry; Kildare; Kilkenny; Laois; Limerick; Limerick City; Longford; Mayo; Meath; North Tipperary; Roscommon; South Dublin; South Tipperary; Westmeath.

Incidentally, it was pretty difficult to find a decent outline map that included Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown, Fingal, and South Dublin, all carved from the former County Dublin in 1994. Come on Intertubes, I expect more up-to-date stuff even though I’m not willing to pay anything for it. Isn’t that how it works?

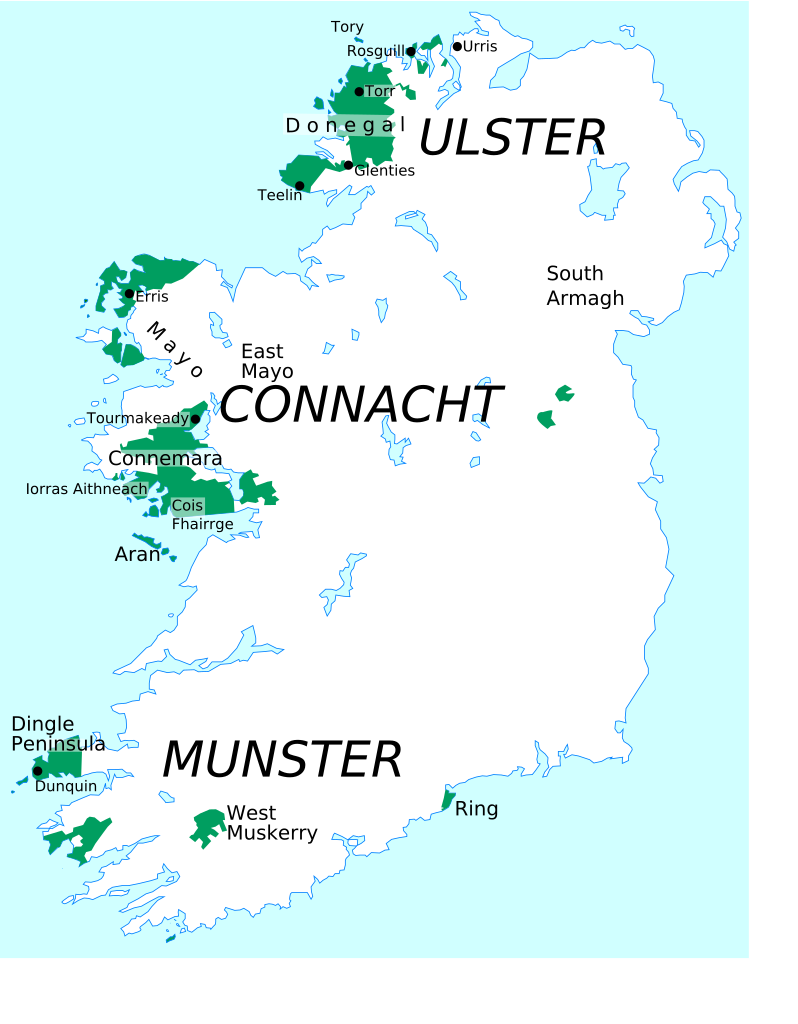

Gaeltacht

The Gaeltacht fascinated me, the small portions of Ireland recognized as Irish-speaking regions. I spent considerable time in the Gaeltacht while on Achill Island and lesser time on the western half of the Dingle Peninsula. My relatives in Limerick also spoke Irish Gaelic fluently. It was the daily household language of older members of the family as they grew-up. One of my relatives even taught the language in a local school. I wondered about that situation so they explained that my 3rd-Great Grandfather came originally from the Dingle Peninsula, from an area still in the Gaeltacht.

Seemingly everyone in the Gaeltacht also spoke English fluently so I never encountered a language barrier other than trying to interpret a thick Irish brogue, and them dealing with my insufferable American accent. The noticeable differences involved road signs as they switched from English to Irish. Still, one could assume rather easily that géill slí meant the same thing as “yield” (or give way) just from the shape and colors of the sign. It never became an issue. Sometimes Irish language road signs appeared randomly outside of the Gaeltacht too, as in this example I found near the Rock of Cashel in Co. Tipperary.

Driving

On a tangent, I think I’ll end the series with a comment about driving in Ireland. Every stereotype about renting automobiles and driving in Ireland is true: lanes were narrower; rarely did they have shoulders; roads twisted preciously; animals or farm tractors appeared at inopportune times; cars parked anywhere they wanted and in either direction; routes always took longer than expected; and as a result, car hires came with astronomically expensive and all-but-mandatory insurance.

Let’s start with the assumption that nobody wants to get into an accident — I don’t think Irish drivers are necessarily any better or worse than anywhere else. The road network itself created dangerous situations. I’ll never complain about US roadways again.

Thanks for reading along with my journey.

Leave a Reply